The Virulent Viral Sextet: #5 and #6 – Eastern Equine Encephalitis Virus and West Nile Virus

#5 - EASTERN EQUINE ENCEPHALITIS VIRUS

What Is Eastern Equine Encephalitis Virus?

How can a horse virus affect people?

Technically, it can’t! Eastern equine encephalitis (EEE) virus is named as such because it is rare in people but more common in horses, often with lethal results.

This virus is spread to people by the bite of an infected mosquito. The transmission happens when a Culiseta melanura mosquito found in freshwater, hardwood swamps primarily on the East or Gulf coasts bites a bird, and then one of the more common mosquitoes bites the infected bird and then an unlucky person. It is not transmissible from one infected person to another except in very rare cases of an organ transplant from an infected person.

Because EEE is rare--with an average of 11 cases a year--it is off the radar for most people except for infectious disease specialists. During an outbreak in Massachusetts in 2019, there were 38 cases, with 19 deaths. Of the 4 cases that year in Connecticut, 3 died and the sole survivor had severe complications, with lasting neurological damage.

These are the kind of concerning results that have experts on edge, especially as those figures are higher than the average death rate of approximately 30%. (That’s bad enough!) And many survivors have ongoing neurologic side effects which may include, according to the CDC, mild to severe intellectual disability, personality disorders, seizures, paralysis, and cranial nerve dysfunction.

Not surprisingly, when a 41-year-old New Hampshire man who’d previously been healthy died in August 2024, alarm bells started ringing. The case is the sixth this year, with the other ones in Massachusetts, New Jersey, Vermont, Wisconsin, and New York. (The NY patient, a resident of upstate Ulster County, tested positive in mid-September and is currently hospitalized.) Some communities are restricting outdoor activities after dusk, and spraying to kill mosquitoes, leaving the locals very unhappy. When my wife and I were in Rhode Island on vacation at the end of August, we received an alert from the local health authorities that they were aerial spraying a mosquito larvicide in local swamps like Chapman Swamp and Great Swamp to reduce mosquito populations and the risk of mosquito-borne diseases like West Nile Virus (WNV) and Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE), which were considered a threat in the region; this was done as a preventative measure to control potential outbreaks. Spraying has been done in NYC and many other areas as well.

What Are the Symptoms and Treatment for EEE?

After getting bitten, the incubation period is 4-10 days. Symptoms can include:

High fever

Headache

Stiff neck

Vomiting

Diarrhea

Seizures

Behavioral changes

Extreme fatigue and/or drowsiness.

Some people who get infected are lucky and have few symptoms that tend to resolve in a week or 2. Those who are unlucky can develop meningitis or encephalitis (brain inflammation and swelling), with severe headache, confusion, seizures, and/or coma leading to death.

There are no vaccines to prevent or medicines to treat eastern equine encephalitis.

Reduce your risk by relentless protection against mosquito bites, especially between dusk and dawn, when the merciless creatures are out in force. When I went to the beach in R.I. (avoiding walking through dunes and grasses), I regularly put picaridin 20% on my skin to repel ticks and mosquitos, as this state is also a hot spot for several well-known tick-borne illnesses, including Lyme, Anaplasma and Babesiosis. But ticks also contain the Powassan virus, leading to Powassan encephalitis, which can be transmitted within 15 minutes of a tick bite. Powassan is a tick-borne encephalitis, which can cause similar symptoms to EEE and West Nile.

There Are 2 Other Mosquito-Borne Encephalitis Viruses

St. Louis Encephalitis virus, found primarily in the Midwest, has very similar symptoms and treatment (as in no available meds) to EEE, but with a lower mortality. From 2003-2023, the CDC reports that there were 304 cases, 207 hospitalizations, and 20 deaths. Fortunately, there haven’t been any reported cases yet in 2024.

Japanese Encephalitis Virus is found in Japan and other western Pacific countries, so Americans are at no risk unless they travel there and visit rural areas for extended periods of time. Approximately 68,000 cases occur each year, but most of them are mild. Less than 1% develop severe symptoms, and these usually lead to neurological disabilities for life, or to death. There is a vaccine but no other treatment other than how you’d deal with the flu.

#6 - WEST NILE VIRUS

What Is West Nile Virus?

If you develop West Nile virus, you’re not alone--it’s the leading cause of mosquito-borne disease in the continental United States. As renowned scientist Dr. Anthony Fauci found out in the summer of 2024, when his case was so severe he was in the hospital for 6 days.

“I really felt like I’d been hit by a truck,” he said in an interview to the online site, Stat. “I have to tell you, I’ve never been as sick in my life. Ever. By far, this is the worst I’ve ever been with an illness.”

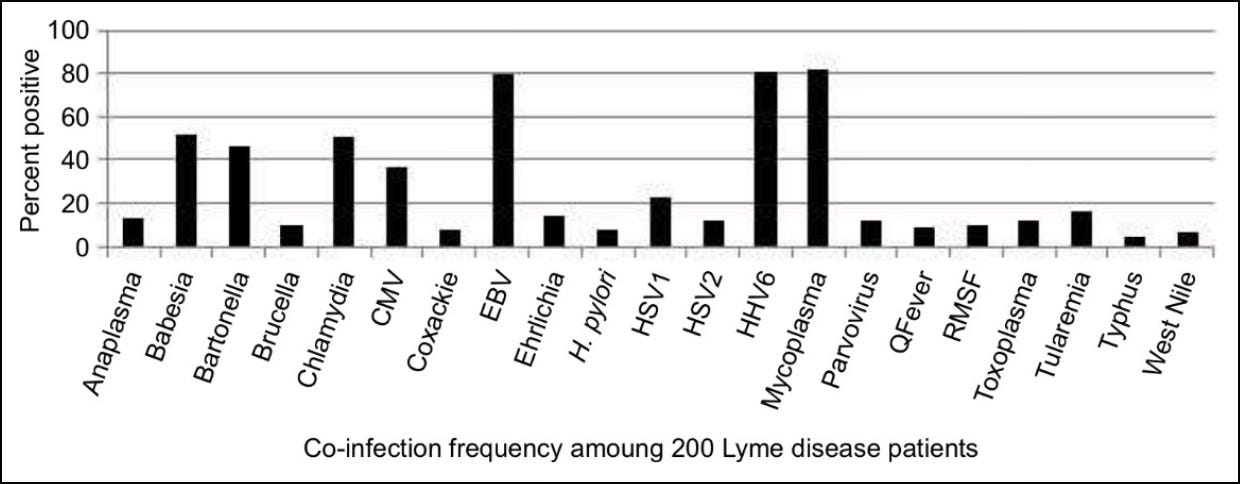

When we tested our patients several years ago for a host of bacterial, viral, and parasitic infections, we found that up to 6.5% of our patients tested had been exposed to West Nile at some point in the past. This was apart from all other bacteria, viruses and parasites.

Many individuals are exposed to West Nile virus and never know it. Because West Nile virus is part of a viral class known as flaviviruses, which include mosquito-borne arboviruses--dengue, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, and Zika--you can be exposed to one flavivirus, and get cross-reacting antibodies to others, looking as if you have been exposed. So, when you want to diagnose West Nile, you have to be sure you are not dealing with cross-reactive antibodies from another flavivirus, as above. And as we discussed in the Medical Detective Substack on dengue, depending on the virus, cross-reactive antibodies can either enhance protection or exacerbate the disease. This phenomenon is called antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE). This explains why some patients who become severely ill from West Nile may have been exposed to another flavivirus infection—that’s what makes them so sick.

What Are the Symptoms and Treatment for West Nile Virus?

Dr. Fauci joined the approximately other thousand of Americans, most of whom are either seniors or immunocompromised, who become so ill with West Nile that they need hospital treatment. According to CNN, “Another 1,500, on average, are diagnosed after developing symptoms, although experts estimate that as many of 80% of infections in the US are never identified.” That’s because, fortunately, most people (8 out of 10) who get bitten don’t get sick or have only mild symptoms. About 1 in 5 people develop a fever and other flu-like symptoms; about 1 out of 150 infected people debilitating and sometimes fatal complications.

These serious symptoms, according to the CDC, include:

High fever

Headache

Neck stiffness

Stupor and/or disorientation

Coma

Tremors

Convulsions

Body aches

Muscle weakness

Vision loss

Nausea and vomiting

Numbness

Paralysis.

The prime season for West Nile is August-September every year. From 1999-2023, the CDC reported that there were 59,141 cases, of which 30,422 were neuroinvasive; 27,617 hospitalizations for all cases; and 2,958 deaths from West Nile virus. So far this year, there have been 659 cases in 43 states, of which 452 had evidence of neuroinvasive disease, the unfortunate kind with more serious side effects. For those who are on the road to recovery like Dr. Fauci, it can take weeks if not months to regain prior strength, and sometimes neurological complications are permanent.

As with EEE, there are no vaccines to prevent or medicines to treat West Nile Virus. There is one drug that, however, that might be useful—ivermectin. Multiple studies done several years ago showed that Ivermectin had potential as a safe and effective drug for Covid, as well as potentially having an effect in other viral infections such as the viral sextet I’ve been writing about here, but conflicting scientific data since then has made the drug seem as if it no longer plays a role in combating viruses. Compounded by the fact that many people self-medicated with Ivermectin meant for horses, not people, which skewed the public’s perception of its safety and usefulness. Not true. Several studies on ivermectin have shown that is has broad anti-viral properties (Yang SNY, et al. 2020). Also, ivermectin has been shown to help control West Nile transmission (Holcomb KM, et al., 2022) as well as being a potent inhibitor of flavivirus replication (Mastrangelo E, et al., 2012). We need to look at all our options, including older, safe drugs, when dealing with these spreading viral infections.

To complicate matters, remember that ticks can also transmit flavivirus infections that can cause encephalitis. Tick-borne flaviviruses include Powassan virus and Tick-borne encephalitis virus, with the lesser-known Louping ill virus and Langat virus, which produce encephalitis on a smaller scale. So, among all of the new, emerging viruses, and older ones increasing in number because of a warming climate, we need to be taking protective measures every time we go outside to make sure we are avoiding ticks and mosquito bites. Especially because West Nile virus can persist in the body even if it doesn’t make you severely ill—there have been cases where it’s still found in the kidneys for up to 7 years (!) according to scientists, and some people have persistent West Nile Virus in their blood, brain, and spinal fluid. Just as we have been finding persistent Covid virus, relapsing Epstein-Barr Virus, and Human Herpesvirus 6 in Covid long haulers, flaviviruses are known as persisters too. Prevention is essential!

We’ve endured the most humid summer on record for this planet. Which creatures are thriving in this heat? Mosquitoes. And ticks.

Protect yourself and stay safe!

References for Ivermectin Studies

Yang SNY, et al. The broad spectrum antiviral ivermectin targets the host nuclear transport importin α/β1 heterodimer. Antiviral Res. 2020 May;177:104760

Holcomb KM, et al. Effects of ivermectin treatment of backyard chickens on mosquito dynamics and West Nile virus transmission. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022 Mar 25;16(3):e0010260

Mastrangelo E, et al. Ivermectin is a potent inhibitor of flavivirus replication specifically targeting NS3 helicase activity: new prospects for an old drug. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012 Aug;67(8):1884-94