Tick season has arrived. The number of bacteria, parasites, and viruses in ticks has continued to rise over the past several decades, and the Powassan virus (POWV) poses a particular risk. Not only can it be transmitted within 15 minutes of a tick bite, but if you get an active infection that invades your Central Nervous System (CNS), called neuroinvasive Powassan encephalitis, there is no known cure. In 40-50% of cases, there are long-term neurological effects.

Powassan is one of several tick-borne viruses that poses significant health risks, along with the Tick-borne Encephalitis Virus (TBEV) in Europe and Asia, and Congo-Crimean Hemorrhagic Fever (CCHF) in Africa, Asia, Eastern and Southern Europe, and the Middle East.

Why Increased Vigilance Is Needed During This Upcoming Tick Season

CBS News recently reported that there’s been an uptick in POWV cases in the Midwest in the last several years. POWV is a tickborne flavivirus infection, transmitted primarily by Ixodes species ticks, including Ixodes scapularis (the deer tick, that also transmits Borrelia burgdorferi, Lyme disease; hard tick relapsing fever, Borrelia miyamotoi; babesiosis; anaplasmosis; and in rare cases, Alpha gal syndrome). It also can be transmitted by Ixodes cookei, the groundhog tick.

TBEV, a similar flavivirus, is present in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Europe, and in Ixodes persulcatus in Asia. CCHF, on the other hand, is caused by a tick-borne virus (Nairovirus) transmitted by Hyalomma ticks. The CCHF virus causes severe viral hemorrhagic fever outbreaks, with a case fatality rate of 10–40%, higher than reported fatalities for POWV and TBEV. This virus causes an Ebola-type illness, also with no known cure. That is why tick prevention is so important.

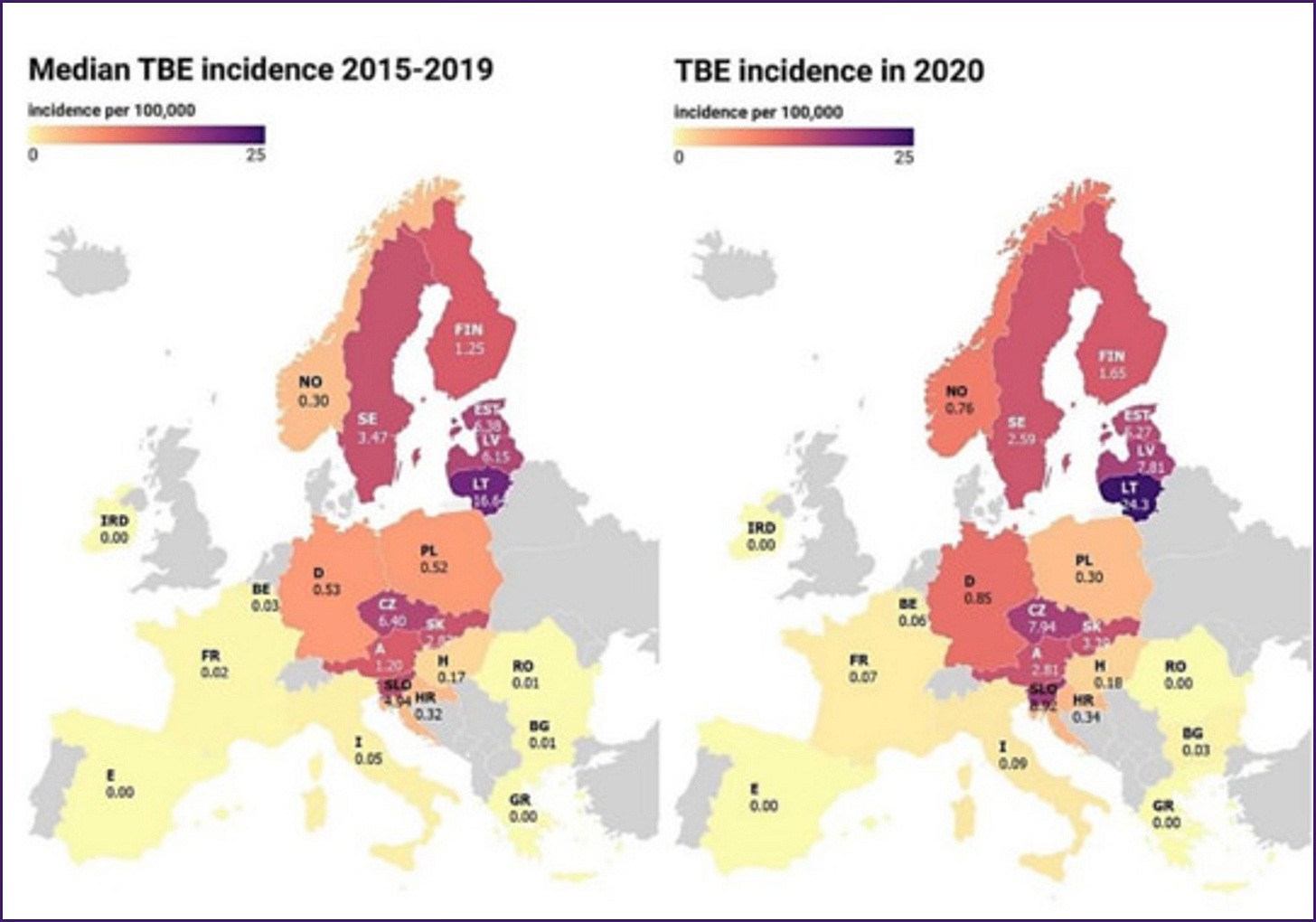

Although most people get a Powassan virus infection in the northeastern US and Great Lakes region, it is spreading due to climate change. Ticks are now more active year-round with the warmer weather, increasing your risk. A recent study from Europe showed that in Lithuania there has been a rise in TBEV, where 11 people died from the disease in 2024. So far in 2025, 10 cases had already been recorded – an unusual development for the winter months. You can see in the map below, recent surveillance data on TBEV in Europe. Red areas are higher risk.

Rates of Infection and How Transmission of These Tick-Borne Viruses Varies

Although all these viruses are tick-transmitted, TBEV can also occur through consumption of unpasteurized dairy products from infected animals. Be careful with those delicious unpasteurized cheeses from France! CCHF can also occur from human-to-human transmission if someone is in close contact with the blood, secretions, organs, or other bodily fluids of infected persons.

Although we don’t hear much about POWV in the United States (125 confirmed cases in the last 25 years), with only about 25 confirmed cases per year, the numbers in Europe for TBEV are much higher, with approximately 10-15,000 cases reported annually. CCHF, on the other hand is rare, but there have been outbreaks in southern Europe. The most recent confirmed CCHF cases were reported in Spain in July and August of 2024, with 3 confirmed cases, all of which were linked to tick bites. There have been several confirmed deaths from the disease.

How Many Ticks Are Carrying These Viruses? What is My Risk?

In New York and Connecticut, POWV prevalence in ticks is typically in the 0-3–4% range. However, many more people in Lyme-endemic areas test positive for POWV antibodies than are actually diagnosed with Powassan encephalitis. In a recent study, approximately 9.5% of samples from those with suspected Lyme with other tick-borne diseases (TBDs) tested positive for POWV, yet in those with evidence of Lyme disease, 17.1% had evidence of a prior POWV co-infection! So infection rates are higher than we suspect, but fortunately, very few people get sick from the virus, as it needs to invade the Central Nervous System to cause systemic illness. Seniors and men seem to have a higher risk of severe disease, along with those with compromised immune systems or severe underlying health conditions.

Symptoms of an Active Viral Tick-borne Infection

The incubation period for POWV is typically 1-4 weeks, with initial symptoms including fever, headaches, vomiting, and generalized weakness. The disease often progresses to severe neuroinvasive conditions such as meningoencephalitis, characterized by altered mental status (ranging from confusion to disorientation), seizures (these are common, and can be a presenting symptom), being unable to speak (aphasia), difficulty moving parts of the body (paresis), movement disorders, and cranial nerve palsies.

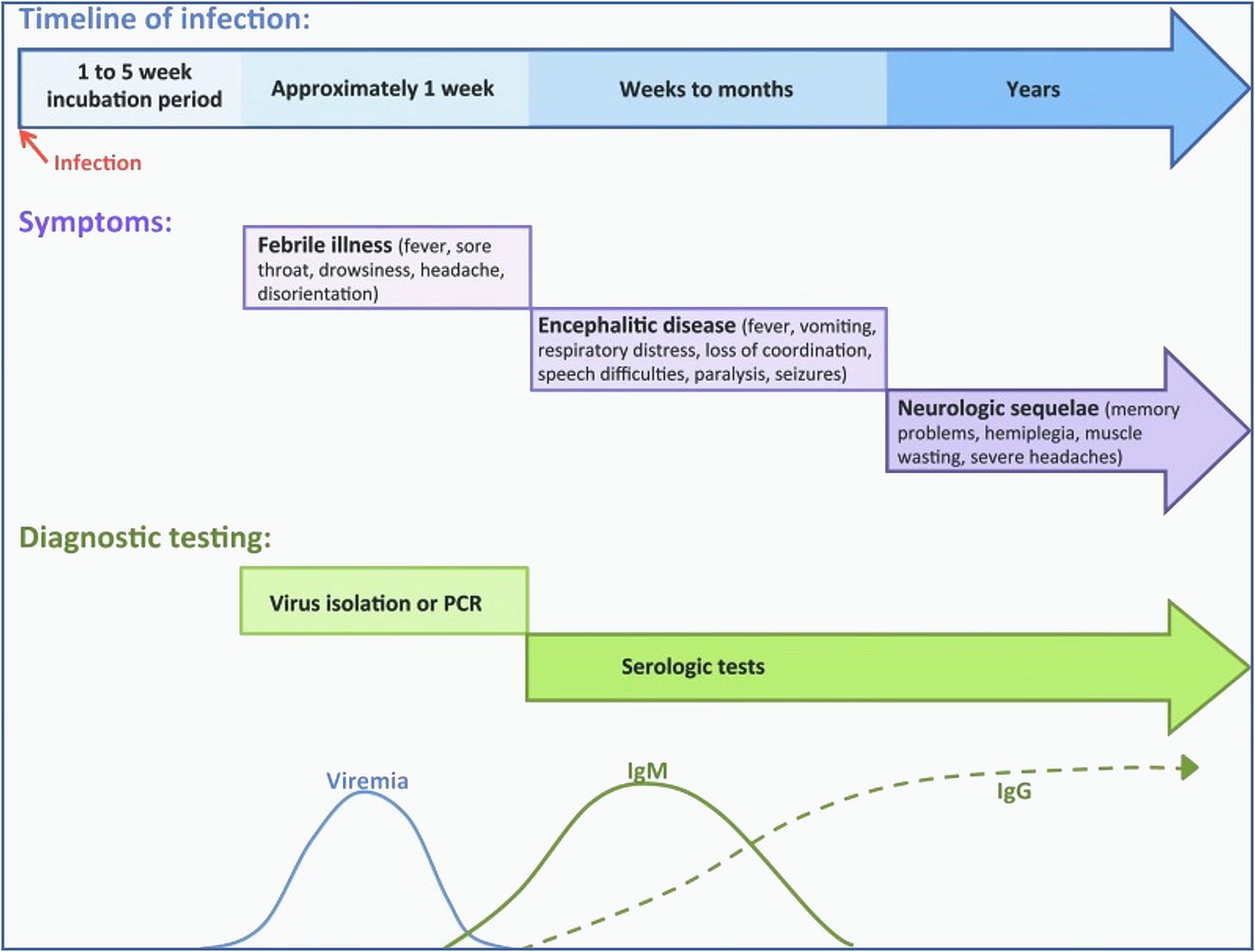

The case fatality rate for neuroinvasive POWV is approximately 10%, and long-term neurological effects occur in over 50% of survivors. See the chart below for details:

TBEV typically presents as a bi-phasic illness. The first phase includes non-specific flu-like symptoms such as fever, headaches, and muscle pains (myalgia). After an asymptomatic period, the second phase involves neurological symptoms like meningitis, encephalitis, or meningoencephalitis. Long-term neurological effects also occur in 40-50% of cases.

With CCHF, following a tick bite, the incubation period is usually 1-3 days, maximum 9 days. The incubation period following contact with infected blood or tissues (as in the case of agricultural workers, slaughterhouse workers, and veterinarians) is usually 5-6 days, maximum 13 days. In CCHF, the onset of symptoms is sudden, with fever, muscle aches, dizziness, neck pain and stiffness, backache, headache, sore eyes, and sensitivity to light (photophobia). There may also be GI symptoms of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain localizing to the right upper quadrant due to liver enlargement (hepatomegaly). These symptoms are followed by sharp mood swings and confusion, often with a fast heart rate (tachycardia), enlarged lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy), and a petechial rash (a rash caused by bleeding into the skin). The petechiae may give way to larger rashes with hemorrhaging.Severely ill patients may experience sudden kidney, liver, or pulmonary failure by day 5 of the illness, with a mortality rate of approximately 30%, with death occurring in the second week of illness. Survivors of CCHF may suffer from post-viral fatigue syndrome, apart from altered mental status, seizures, and meningoencephalitis.

Differential Diagnosis of Meningitis or Meningoencephalitis After a Tick Bite

There are many different causes of meningitis, which can be viral, bacterial, fungal, and even parasitic. The differential diagnosis for meningitis and Bell’s palsy therefore goes beyond Lyme disease and Bartonella! Borrelia miyamotoi has been associated with a meningoencephalitis, particularly in immunocompromised patients, and common tick-borne infections like Ehrlichia, Anaplasma and Rickettsia can also cause meningitis or meningoencephalitis (Rickettsia typhi, being the primary culprit). Bartonella can similarly cause a meningitis, meningoencephalitis, Bell’s palsy, and new onset of seizures, as can other tick-borne viruses, like Colorado tick fever virus, causing meningoencephalitis in children. A broad differential diagnosis is therefore needed in someone presenting with meningitis and meningoencephalitis. Some of these infections are also present in the blood supply and are rarely transmitted after a blood transfusion.

Mosquito-borne Causes of Meningitis and Encephalitis

Mosquito-borne infections like West Nile and Zika, similar flaviviruses to POWV and TBEV, can also cause neuroinvasive disease with meningitis and encephalitis (West Nile in 1/150 infected individuals). While dengue virus is primarily known for causing dengue fever (break-bone fever) it can also lead to neurological complications such as encephalitis and meningitis. St Louis Encephalitis Virus, Eastern Equine Encephalitis Virus) La Crosse Virus, Japanese Encephalitis virus, and Chikungunya Virus are also known causes of inflammation in the CNS. These tick-borne viruses and mosquito-borne viruses have a significant impact on public health. Over 6% of my patients had been exposed to the West Nile virus. See my prior Substack on dengue fever for more information: https://medicaldetective.substack.com/p/the-virulent-viral-sextet-2-dengue?r=21mpl as well as my other Substacks on dangerous viruses.

Testing for POWV, TBEV, and CCHF

Diagnosis of POWV infection is primarily based on detection of an IgM ELISA in serum or cerebral spinal fluid, confirmed by the plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT). A fourfold rise in POWV antibody titers in someone recovering from the virus (a convalescent sample), or direct detection of POWV by virus culture or molecular detection method also confirms exposure. Direct detection methods involve viral RNA (RT-PCR) testing in acute cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) specimens or tissues, which is also the best diagnostic test for CCHF. When a spinal tap is performed, the CSF analysis typically shows elevated lymphocytes (similar to a lymphocytic meningitis seen in Lyme disease), mildly elevated protein, and normal glucose levels. A brain MRI may reveal deep foci of increased inflammation, and an EEG will typically show diffuse slowing and focal abnormalities. TBEV blood testing also relies on detection of TBEV-specific IgM and IgG antibodies in serum and CSF. IgM-capture ELISA is almost always positive in the neuroinvasive phase of the illness.

What About False Positive Tests from Other Flaviviruses?

Viruses in the flavivirus genus like yellow fever virus, dengue, West Nile virus, and Zika virus can cross react with POWV, and this infection can be difficult to diagnose where other flavivirus infections are prevalent.

Treatment Options

There is no specific antiviral treatment available for a POWV infection. Management may involve hospitalization, intravenous fluids, respiratory support, and medications to control seizures and reduce intracranial pressure. Potential treatments being explored include the development of new small-molecule antivirals (like ribavirin) and monoclonal antibodies. While ivermectin has been shown to be able to inhibit the replication of several flaviviruses, including TBEV in culture, these results have not yet shown clinical results.

Glutathione (GSH) does, however, have potential in treating flavivirus infections. It lowers inflammation and inhibits viral replication. Blocking NFKappa B, using NAC 600 mg 2x/day, Alpha lipoic acid 600 mg 2x/day (be careful if you have reactive hypoglycemia, use lower doses) and GSH (minimum 500 mg 2x/day), can help with viral replication. Other immune support, pDC Activate, has a novel mechanism of action that stimulates immune function in the GI tract for broad-range immune support (shown to be helpful in those with Dengue). In those with chronic Lyme, Bartonella, mold and/or long COVID, who may have B and T cell immune dysfunction, supporting immunity may be also helpful.

Unanswered Questions and Directions for Future Research

Flaviviruses like West Nile and Zika can persist in the body for months to years. There is evidence that POWV can persist in the body for up to 84 days post-infection, but it is believed to be lingering RNA, not active virus, that causes chronic CNS inflammation. But what happens with POWV exposure in immunosuppressed Lyme and Bartonella patients who have mold toxicity and long COVID further impacting their immune function? Can the virus persist in immunosuppressed hosts?

This is an important research question that needs to be answered. If we remove the immunosuppressive mold toxins, and adequately treat the infections and overlapping medical problems (as in the case of dapsone combination therapy and addressing MSIDS variables), will that improve our risks of not getting neuroinvasive POWV? If we do get it, will that approach improve long-term potential side effects?

Since viruses like POWV activate brain glial cells and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, contributing to neurodegenerative effects and neurological after-effects, we need more research into whether blocking inflammatory pathways like NFKappa B (NAC, ALA, GSH) and NLRP3 inflammasomes (LDN, low dose melatonin), while stimulating anti-inflammatory pathways like NRF2 (curcumin, sulforaphane, resveratrol, green tea) can also prevent long-term after-effects from the virus.

Finally, there is a safe and effective vaccine for TBEV in Europe--but none for POWV or CCHF. Studies on the TBEV vaccine showed an effectiveness of 92% across all age groups, significantly reducing severe disease, hospitalization, and death, with an excellent safety profile. Since we need protection against a broad range of TBDs, we should be working on a safe and effective tick-spit vaccine and getting it to market. Then if we get a tick bite, antibodies to the tick’s saliva will cause it to immediately fall off before we get ill.

From POWV or any tick-borne disease!

Come hear my interviews on viral infections and TBDs with Dr Jacob Teitelbaum (CFS/ME, FM expert) and Dr Bruce Patterson (Long COVID researcher) during the 2025 Healing Lyme Summit 2.0. It is free to attend: https://drtalks.com/summit/lyme-summit/?oid=94&ref=3029